Plan A Paeds

Paediatric Plan A Blocks were proposed by Annabel Pearson et al in a recent editorial in Anaesthesia (Jan 2023). This section of the website is dedicated to material improving access to regional anaesthesia for paediatrics.

Introduction

Dear Colleague,

Welcome to the Paediatric Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anaesthesia section of the RA-UK Website. This resource is a collaboration between RA-UK, APAGBI, CPAS and ESPA to provide up-to-date guidance on the performance of ultrasound-guided regional anaesthesia in children. It has been developed by a group of practising paediatric anaesthetists with a special interest in regional anaesthesia and aims to provide a succinct guide to performing regional anaesthesia in children.

Regional anaesthesia is such an important and beneficial technique in children that it should be considered for all appropriate cases, balancing the advantages against the potential risks. However, it can only be utilised by caregivers with the correct anatomical knowledge and after suitable training. In addition, access to the correct equipment and assistance are important. When performing more complex regional techniques and/or catheters, an on-site acute pain service needs to be established.

The information follows the Plan A block principles for paediatrics with the aim of providing a safe and versatile reference for those starting on their journey in paediatric regional anaesthesia. The format for each block will cover all aspects from indication through performance to complications. The Plan B/C/D blocks are aimed at those confident in the basics who want to develop more advanced techniques for more complex surgeries.

We are keen for feedback to improve the website, so please email us your suggestions to support@ra-uk.org

Best wishes,

Babette Clinck, Annabel Pearson, Catalina Stendall, Nadia Najafi

On behalf of RA-UK, APAGBI, CPAS and ESPA.

We would like to thank our expert writing group who have contributed to the project - see acknowledgments

All images are provided with appropriate consent and are copyright to RA-UK, APAGBI CPAS and ESPA.

Please contact support@ra-uk.org

Basics

Superior analgesia results in:

- Less stress for patient/parents/caregivers/staff

- Less opioid requirement

- Less opioid-induced side-effects such as constipation, nausea and vomiting, itching, urinary retention

- Less risk of postoperative opioid-induced respiratory depression and apnoea

- Less respiratory support needed (reduced pain-related shallow breathing after abdominal/thoracic surgery)

- Less hormonal stress response

- Reduced risk of an excessive deep plane of general anaesthesia

- Smoother emergence

- Less depressant cardiovascular effects of anaesthetic drugs

- Less potential adverse effects on the developing brain

- Reduced incidence of emergence delirium

- Faster return of gut function and appetite and therefore faster eating and drinking postoperatively

- Faster mobilisation postoperatively, improved compliance with physiotherapy

Use of ultrasound results in:

- Rapid discharge/reduced length of stay

- Imaging of anatomical structures without ionising radiation

- Straightforward learning curve

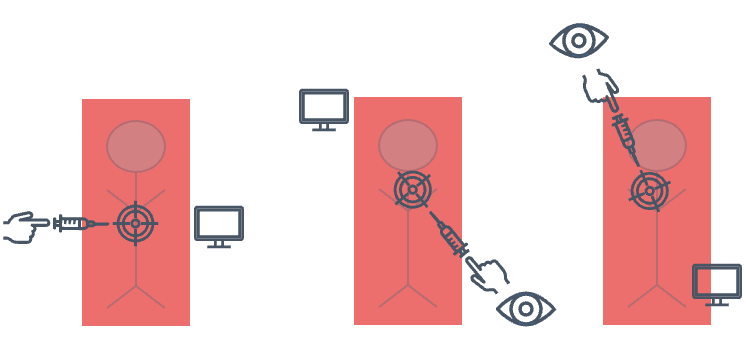

- Live visualisation when performing needling procedures:

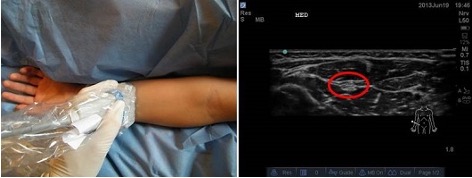

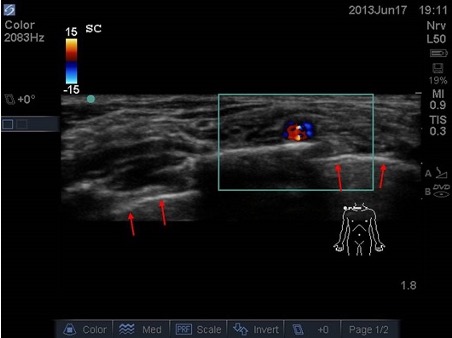

- Identify targets (nerves, fascial planes) – example 1, median nerve to the forearm

- Identify nearby structures (blood vessels, bowel, bone, pleura) which allows you to avoid complications (especially in small children where target structures and nearby structures are in immediate proximity or very superficial) – example 2, supraclavicular plexus in neonate: very little space between plexus, vessels, pleura, ribs.

- Select best needle approach, real-time information to guide needle insertion, accuracy of needle tip placement

- Insight into the anatomy of the individual patient (detect anatomical variations)

- Possibility to safely perform blocks in the presence of neuromuscular morbidities (landmark technique can be difficult in e.g. myotonia, muscular atrophy) or neuromuscular blockade (neuromuscular stimulation technique can be unreliable).

- Observation of the spread of local anaesthesia; ultrasound (US) allows 30-50% lower doses to be successfully used. Reduced risk of intravascular injection

- Literature shows faster onset times, greater block duration and improved post-operative pain scores in comparison to blind technique

- Most blocks in children are performed when under general anaesthesia which provides excellent conditions to perform a block

- Children are generally smaller than adults and have less subcutaneous tissue, which means a more superficial location of the target areas for the blocks. This allows the use of a high frequency probe for a more detailed image and allows a flatter needle trajectory and therefore improved visualisation of the needle tip

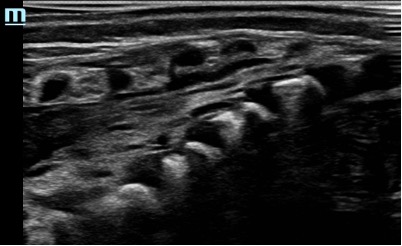

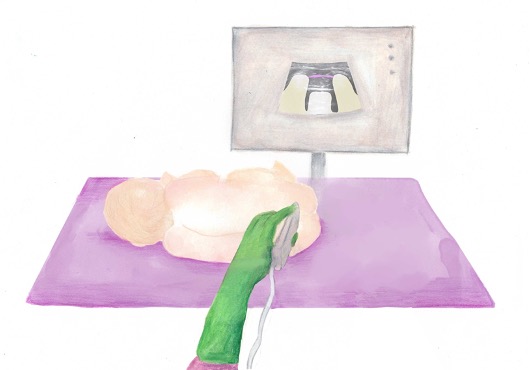

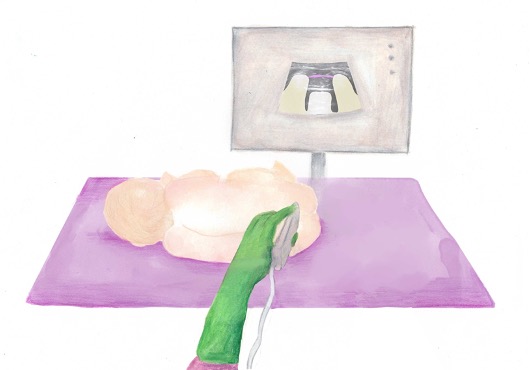

- At birth, the ossification centres of the spine are at an early stage of development; it is therefore possible to obtain excellent spinal images in neonates. With age and increasing ossification, the US window to the spine diminishes (the ossification is complete at 21 years old)

Caudal in a neonate

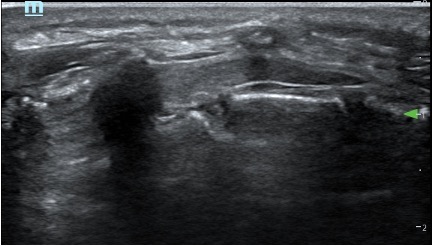

Caudal in a two year old

Risks associated with regional blocks in children

Nerve injury

- Most US techniques in children are performed under general anaesthesia. Large studies have demonstrated that this is safe practice, and it is the recommendation from ESRA/ASRA. However, awareness that this could potentially mask complications, like intraneural injection, is important

- Large prospective databases have shown a low complication rate in paediatric regional anaesthesia. Nevertheless, there is less literature exploring regional techniques in children or detailing paediatric anatomy, particularly in children with congenital disorders or neuromuscular conditions, when compared to adults.

- Following a nerve block, some children may experience a patch of skin exhibiting a prolonged numbness or a tingling sensation. Typically, this is self-limiting and tends to improve within a few weeks, though it might persist for up to one year. Permanent nerve damage is exceptionally rare and precise numbers are not known. In adults it is estimated to occur in 1 out of 2,000-5,000 nerve blocks. A recent study examining over 100,000 blocks in children demonstrated a temporary nerve damage incidence of 2.4 per 10,000 patients, with no cases of permanent nerve damage identified.

Local anaesthetic toxicity (LAST)

- Be aware that a general anaesthesia might conceal the early (neurological) signs of LAST

- Neonates and infants are particularly vulnerable to the risk of LAST. The physiological immaturities of the neonatal liver in association with a relatively high cardiac output produce pharmacological differences that combine to increase the risk of local anaesthetic toxicity in neonates.

- Most common when performing blocks in a highly vascularised area (brachial plexus, caudal, penile block) or when combined with local infiltration by the surgeon (ensure the total concentration of local anaesthetic administered, does not exceed the maximal safe dose )

Infection

- Maintain strict adherence to sterility protocols when performing a nerve block

- Risk increases with prolonged use of catheters (> 3 days)

NB: Studies have demonstrated an increased overall risk for complications when performing central blocks in children compared to peripheral block, but the use of ultrasound reduces risks for complications.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Absolute contraindications

- Patient or parent refusal

- Local anaesthetic allergy

- Infection at the proposed needle insertion point

Relative contraindications

- Coagulopathy or on anticoagulants – block dependent (see EJA guidelines 2022)

- Challenging anatomy at site of the block

Block specific contraindications (see individual block sections)

CONSIDERATIONS

- Pre-existing nerve damage

- Compartment syndrome: the concern is that blocks could mask the pain associated with compartment syndrome and thus delay diagnosis. However, there is no evidence to support NOT doing a block in children.

Recommendations regarding compartment syndrome (See also ESRA/ASRA guidance 2015):

- Discuss with the surgical consultant to identify high risk cases

- Discuss with parents/child, discuss risks and benefits of the block and symptoms of compartment syndrome

- Use low concentration of LA (e.g.0.125% of levobupivacaine or 0.1% of ropivacaine)

- Don’t use any additives (not even dexamethasone)

- The surgical consultant needs to consider inserting a compartment pressure monitoring device

- Postoperative vigilance

THE PROVIDER

- Strong knowledge of anatomy

- Appropriate training

- Appropriate assistance

PATIENT FACTORS: ELIGIBLE FOR BLOCK?

- Type of surgery

- Choose the appropriate block (+/- catheter or additives)

- Contra-indications for LRA techniques

- Relevant comorbidities which can make regional techniques more difficult

- Conditions that make US imaging difficult: e.g. cerebral palsy – contractures, long-term wheelchair dependence, muscle atrophy (poor muscular structures on US)

- Conditions that make central blocks difficult: Scoliosis

- Conditions that make peripheral nerve block (PNS) techniques difficult: myotonia, use of neuromuscular blocking agents, Ehlers Danlos (a block can also cause skin damage), hereditary sensory and motor neuropathy (HSMN) 1 and 2 (may require higher mA when using PNS technique with a nerve stimulator)

- Previous LRA experience

- Neuromuscular conditions (assess and document before performing the block)

- History of chronic pain in area to be operated on; consider LA catheter /additives

- Patient on baclofen: increased risk of muscle spasm postoperatively: consider LA catheter/additives

- Sometimes longer analgesia is desired to facilitate physiotherapy: consider LA catheter/additives

NB: Before placing a catheter, consider where they will be nursed postoperatively. Consider use of spica/casts when considering catheter exit site.

The extent of surgery is not always known beforehand. Sometimes it is better to provide intraoperative intravenous analgesia/do a single shot block and perform/repeat the appropriate block at the end of the surgery.

PREOPERATIVE CONSULTATION

Check the proposed injection site beforehand if possible

Record the patient’s weight -> Calculate maximum dose of LA (2.5 mg/kg)

Discuss analgesic options with patient/parents: risks and benefits, realistic expectations, alternate block should primary choice be undeliverable, back-up analgesic plan in case the block fails

Explain the feeling of “pins and needles”

Get informed consent from patient/carer – patient information leaflet

NB: Generally, the more peripheral a block is, the better the risk-benefit balance, and thus more acceptable to the patient and parents/carers.

In older children having minor surgery the operation may be done awake; have EMLA applied to the block injection site (you may wish to scan the patient on the ward prior to this). If a parent/carer is going to attend, ensure they know what their job is in the anaesthetic room i.e., distracting their child during the proceedings. Ensure a nurse will be attending the procedure to support the patient and the parent/carer.

IN ANAESTHETIC ROOM

- Full and appropriate (AAGBI) monitoring, secured airway and IV access

- If prophylactic antibiotics indicated for surgery, then administer prior to the block

- Position patient safely in block position

- Consider ergonomics: Position yourself and the ultrasound machine to align your needle, ultrasound probe, the targeted area on the patient and the ultrasound image in a single straight line

- The comfort of the operator will increase the likelihood of a successful block: consider whether to sit or stand, the appropriate bed height and the position of the patient. Ensure you stand square, keep shoulders perpendicular to the needle, elbows close to your sides; this all reduces the tendency to drift out of alignment

- Assess surface anatomy

- Choose appropriate ultrasound probe and block needle

- For all blocks: wear sterile gloves and use a probe cover

- For continuous catheter techniques and more central blocks: full aseptic technique is required (hat, mask, gown, gloves), sterile probe cover

GETTING READY

- Clean a large area around the desired injection site (e.g., a 2% chloroprep stick) and drape the patient exposing a large enough area to allow scanning up and down the nerves

- Allow the area to dry completely

- Choose appropriate % LA. Do NOT draw up more than the maximum dose

- Connect the extension to the needle, ensure all the kit is flushed through – air bubbles distort the ultrasound image. If using a catheter, flush to ensure patency

- Consider the use of adjuvants

NB: usually 0.25% levobupivacaine (or 0.2% ropivacaine) is used, 0.5% is appropriate for ring blocks, penile blocks and for lower limb surgery where there is high risk of postoperative muscle spasm.

Use a lower concentration (e.g., 0.125% levobupivacaine or 0.1% ropivacaine) if there is high risk of compartment syndrome or local anaesthetic toxicity (e.g., neonates)

If concerned about the volume of LA available due to the small size of patient (< 10kg), draw up a separate syringe with saline to use as a ‘seeker solution’ to ensure needle tip position before injecting LA. This will avoid wasting LA due to incorrect needle position.

When performing a central block or inserting a regional catheter, a full surgical scrub is necessary (gown, gloves, mask, …)

ULTRASOUND IMAGING

- Choose appropriate probe (usually high frequency linear, though a curvilinear is preferred for deeper blocks in larger patients e.g., Anterior Quadratus Lumborum block). Choose the highest frequency appropriate for the estimated depth of the block

- Orientate probe and image, set the depth greater than the expected target depth

- Optimise the gain (vessels must be black and the rest uniform grey)

- Use sterile US gel to provide an air free interface (remove gel prior to needling)

- Perform a mapping or scout scan to assess the anatomy and identify the target

NB when sliding up and down with the probe, allow the ulnar side of you hand to maintain contact with the patient. This will give you more control over your scanning and prevents the probe from slipping off. Tilting the US probe cranially or caudally can make the nerve easier to visualise (this allows for the anisotropic behaviour of the nerve)

NEEDLING

- Perform a “Prep Stop Block” or “STOP BEFORE YOU BLOCK”

- For in-plane techniques (IP): Place the target in the lower corner opposite to the needle entry point, ensure your needle tip is always visible when advancing the needle towards the nerve. Aim for the 6 o’clock position (= deep to the nerve), aspirate, then slowly inject LA. The LA will show as darker spread around the nerve. If, when half of the LA is injected, the nerve does not look surrounded, it may be necessary to withdraw the needle and inject the 2nd part of the LA at the 12 o’clock position (superficial to the nerve).

- For out-of-plane techniques (OOP): place the target in the middle of the screen. The targets will be 3 o’clock and/or 9 o’clock (either side of the nerve). Follow your needle tip. Always aspirate before injecting.

- For large nerves (e.g. the sciatic) a “doughnut sign” is desirable. This is not necessary for smaller nerves

- Insert the needle with bevel facing towards the ultrasound probe

Where possible try not to contact the nerve with the needle, this can often be achieved by getting into a fascial plane close by, then allowing the injectate to actively be pushed towards the nerve.

If you lose the view of the needle, stop immediately and check your probe and needle orientation. Use your probe to find your needle tip while keeping your needle immobile. Do NOT try to move your needle towards the ultrasound beam.

INTRAOPERATIVELY

- Assess any deficiencies in the block: observe changes in HR, BP and RR; avoid using anaesthetic agents (e.g., opioids) that may obscure assessment (especially true in children with special needs where pain will be very hard to assess in recovery - you need to know your block works/doesn’t work)

- Ensure systemic analgesia is provided for procedures where the block does not cover visceral pain (e.g., rectus sheath block for pyloromyotomy)

- Consider systemic analgesic adjuvants (e.g., MgSO4, dexamethasone, NSAIDS, alpha-2-agonists)

POST OPERATIVELY – FIRST STAGE RECOVERY

A well working regional technique should provide ideal conditions for a child in recovery; pain-free, alert, free from nausea and vomiting

If there are doubts regarding analgesia, consider giving a small dose of a fast-acting opiate e.g., 0.25mcg/kg of fentanyl or 0.2-0.3mg/kg of ketamine. If the block is effective, the child will immediately settle.

If doubts remain regarding the efficacy of your block, it may be prudent (operation dependent) to consider additional analgesia e.g., systemic opiates in the form of an NCA or PCA-pump (nurse-controlled or patient-controlled analgesia)

All patients should be written up for regular simple analgesia such as regular paracetamol and/or ibuprofen (as appropriate) and alternative systemic analgesics should be prescribed as rescue analgesia. When the block wears off, these will reduce the risk of ‘rebound pain’.

Post-operative monitoring of the block is imperative (by the ward nurses and by the acute pain team) to identify any issues early, including:

- Local anaesthetic toxicity (e.g., with continuous LA infusions)

- Infection of the block site

- Compartment syndrome (See ESRA/ASRA guidance 2015)

NOTE: It can be difficult to distinguish pain from emergence delirium or in fact just the displeasure of being in the theatre environment, the “pins and needles” sensation or the presence of dressings/cast. The help of an experienced recovery nurse and parent aids diagnosis.

Plan A Blocks - Peripheral

Plan A Blocks - Central

Infraumbilical and lower limb surgery

e.g. hypospadias, bilateral inguinal herniotomy, bilateral orchidopexy, bilateral lower limb surgery, anorectoplasty

Useful for bilateral surgery in small children where the weight-based volume of local anaesthetics is limited. It provides a dense block and can significantly reduce the need for opioids and the doses of general anaesthesia. However, compared to a peripheral block, a caudal block carries more risk, and the duration of the analgesia will be shorter.

Considerations

Is a central block –> so consider other (more peripheral) blocks

Level of block = volume dependent;

NOTE: in children > 2 years the cephalad spread of LA is unpredictable + they may not appreciate the sensation of numbness/pins and needles –> consider alternative block

Possible hypotensive response due to vasodilatation of the lower limbs

Urinary retention

Motor block lower limbs

Contraindications

See general LRA CI

Spinal dysraphism (see cutaneous stigmata and US image)

Severe coagulopathy

Increased intracranial pressure

Caution with

Spinal stenosis patients

Hypovolemic patients

Complications

Intravascular injection -> risk of Local Anaesthetic Systemic Toxicity (LAST)

Intrathecal injection -> total spinal anaesthesia

Failure or inadequate block

WHY ULTRASOUND

The conventional approach for performing a caudal block has historically involved the use of a landmark technique, which remains the predominant method to date. Nevertheless, ultrasound presents an opportunity to enhance the safety and effectiveness of this procedure.

- It helps in identifying spinal dysraphism (contraindication for the block; see image library)

- It aids in identifying the correct location for needle insertion and will subsequently confirm the needle tip position when injecting

- It visualises the caudal sac and thus will prevent intrathecal injection.

- Utilising saline for the initial injection reduces the likelihood of intravascular administration of local anaesthetic, thereby minimising the risk of local anaesthetic toxicity.

- It allows you to follow the spread of the local anaesthetic and confirm the level of the block.

The caudal epidural space is the lowest section of the epidural space and is entered through the sacral hiatus, which is still accessible in children as the lamina of S5 (and/or S4) have not yet fused.

The dural sac finishes at L2-L3 (T10-L3) in term infants (L4 in preterm infants) and L1 in children >1y old (= adult level).

Left lateral decubitus with legs drawn up to chest

Palpate the sacral cornua on either side of the midline as this will be your starting point for the ultrasound approach

Take care to avoid heat loss during the procedure.

Ultrasound probe selection: linear high frequency probe

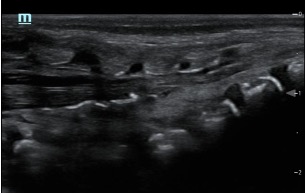

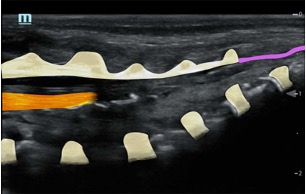

Mapping/scout scan: look between the intervertebral spinous processes and laminae:

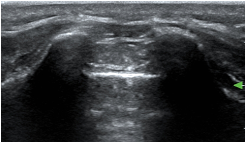

1)Probe position transverse over the sacral cornua (-> frog’s eyes US view)

2)Then rotate probe 90 degrees for a longitudinal view

Identify:

•Sacral cornua

•Sacrum

•Sacrococcygeal membrane

•End of the dural sac (hyperechoic (<-> CSF are anechoic (black)

•Caudal epidural space

•Assess the position of the dural sac in relation to the sacrococcygeal membrane

NOTE: Ultrasound can't see through bone; so with increasing age (= increasing angulation of the spinous processes and increasing ossification of the laminae) the size of the echo window will diminish -> you might need to scan paramedian

TIP: use a large linear probe (50mm) – this will allow you to visualise more vertebrae in one image for easier monitoring of needle approach and LA spread

Use a 22G cannula (24G in neonates)

Target depth: 1-2 cm

Remove gel at insertion point

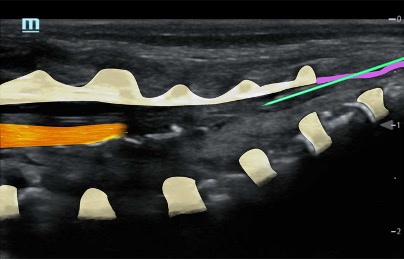

Needle insertion at the apex of the sacral hiatus at an angle of 45⁰ until resistance

Reangle to 30⁰ and insert another 5mm (advance under US vision) – characteristic pop through ligament

Then slide the cannula off the needle (it should slide off easily)

Remove needle, open cannula to air and observe for blood or CSF, then aspirate with a 2ml syringe

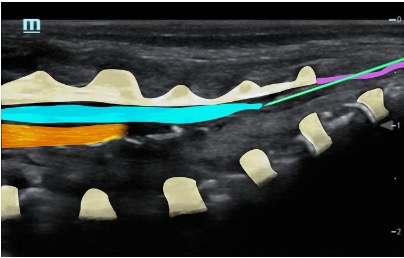

Perform saline test à Confirm position (saline expands the epidural space and pushes the dura more anteriorly)

NOTE: If the injectate is not visualised, the LA might be going intravascular or outside of the caudal canal; STOP and reposition the needle.

Slowly inject LA and observe spread (aspirate repeatedly)

Levobupivacaine 0.25% max 1ml/kg (+/- clonidine 1mcg/kg for increased duration)

Track the LA spread by sliding the probe cranially (probe positioned paramedian longitudinally); ensure the appropriate level is reached for the intended operation

NOTE: Level of the block will correlate to injected volume

NOTE: For neonates 0.125% levobupivacaine is effective and allows a greater volume to be injected should a higher level be desired (and an alternative technique e.g. direct thoracic epidural or caudal catheter is considered less appropriate)

NOTE: Caution with the use of adjuncts in neonates – clonidine will prolong the block but can cause an increased risk of apnoeas, particularly in premature neonates